by Anissa Patel

SPECIAL TO EASTBOSTON.COM

Green never used to be my favorite color. I grew up in the suburbs, taking for granted the hundreds of acres of conservation land that I lived behind. Now, as a high school senior at the Winsor School in the heart of the Longwood Medical Area, I’ve discovered that my everyday color palette has changed from earth tones to drab metallic greys and beiges. Summer days are sweltering, pierced by the everpresent ambulances and car horns.

There’s an obvious, underappreciated fix. Trees.

Urban tree canopies serve a purpose deeper than aesthetics—they are a critical part of urban infrastructure, just as much as sidewalks and buildings. Their shade and biological processes reduce heat and stormwater flooding and lower carbon levels. They also provide habitats for wildlife and improve mental health for those living in the city. Without a doubt, they are an excellent reason for green to be my favorite color.

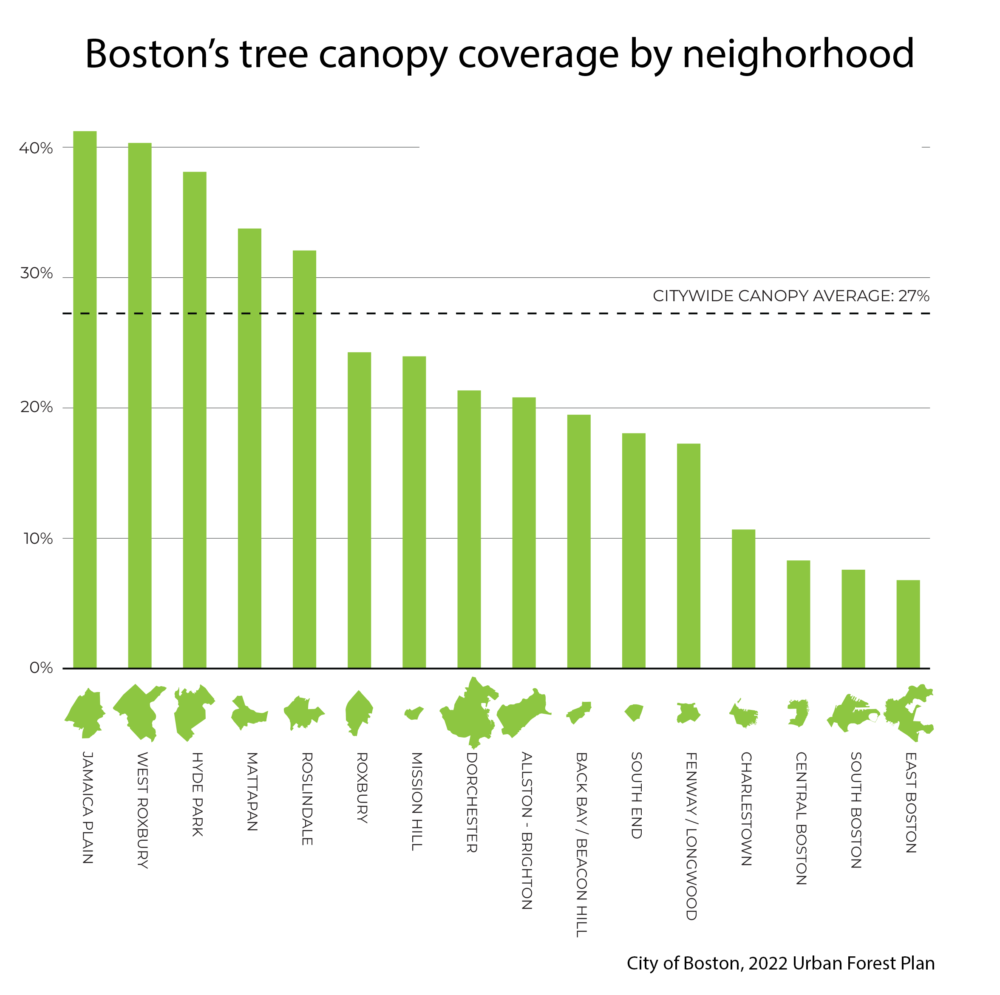

Currently, 27% of Boston has canopy cover. This may seem like a significant amount at first glance, but it is important to remember that each neighborhood’s canopy percentage varies. For example, Jamaica Plain has 43% coverage, while East Boston has only 7%. This large disparity is the cause of a 10-degree difference between daytime and nighttime temperatures in those neighborhoods. In addition, historic inequities such as redlining and structural racism create an inequitable distribution of the tree canopy. Many low-income and minority communities, such as in Allston and Eastie, have decreased access to green space and higher exposure to pollutants and heat risks.

When I learned these statistics, I asked myself: what is the Boston metropolitan area doing to create a more equitable tree canopy? To start, the City of Boston released an Urban Forest Plan in 2022 outlining its strategy to expand and distribute the canopy more equitably. They will create space to plant more trees, prioritize street tree planting, and assemble maps that overlay demographic information with tree canopy levels to determine disparity. In tandem, the city will more than triple the number of city employees focused on trees (from 5 to 16) and form a new forestry office.

However, more than just bureaucratic action, I believe the city itself must help citizens reckon with what matters most to them. Increasing the tree canopy will lead to structural changes in the appearance of our metropolitan communities, whether through micro-forests or reducing street parking. Residents in these underserved, minority, and low-income neighborhoods must grapple with the choice: change their community infrastructure or continue with their status quo. Effective understanding of and advocacy for this choice can only be accomplished with a two-pronged approach: streamlined avenues of communication and a public awareness campaign.

Streamlined avenues of communication are essential to any equitable process. The movement to increase the urban tree canopy is driven by multiple sectors: the city, non-governmental organizations, and citizen groups, among others. Without frequent communication between all parties, inclusion cannot be sustained. The city must create an online space in collaboration with leaders of these different sectors where data, reports, and maps are made readily available.

Public input on the urban tree canopy movement is often compromised by the lack of understanding about the short- and long-term value that the canopy provides. There is also a lack of knowledge on the care and maintenance of trees, such as planting and pruning, which is notable given that 50% of Boston’s tree canopy is on private property. So just like the city would for a new public building or park, trees must have their own marketing team. Their role as public infrastructure is just as critical as any other facet of the urban environment, perhaps even more so.

It isn’t just up to the city; environmental justice work is for everyone. Without intervention, all Bostonians, particularly the environmental justice communities of Boston, will feel the effects of climate change more acutely. Let’s bring earth tones back to the color palettes of all of our lives—they will make us stronger, happier, and healthier.

Works Cited

Bebinger, Martha. “Boston’s Mayor Wu Announces Investment in Trees for Cooling, Flood Reduction and Beauty.” WBUR, 21 Sept. 2022, www.wbur.org/news/2022/09/21/boston-mayor-wu-invests-in-trees-for-cooling-water-savings-and-beauty-climate-change. Accessed 9 Jan. 2023.

“Boston Tree Equity Maps.” Speak for the Trees, 2023, treeboston.org/tree-equity/. Accessed 11 Jan. 2023.

Environmental Justice Strategy. Massachusetts State Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, Oct. 2022. Mass.gov, www.mass.gov/doc/environmental-justice-policy6242021-update/download. Accessed 9 Jan. 2023.

“Speak for the Trees, Boston: Growing Boston’s Urban Tree Canopy.” Climate Change Response Framework, NIACS, 2023, forestadaptation.org/adapt/demonstration-projects/speak-trees-boston-growing-bostons-urban-tree-canopy. Accessed 9 Jan. 2023.

Urban Forest Plan. City of Boston , 21 Sept. 2022. Boston.gov, www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2022/10/2022%20Urban%20Forest%20Plan%20-%20single%20page.pdf. Accessed 9 Jan. 2023.

Anissa Patel is a senior at the Winsor School who writes on environmental justice and policy issues. She can be reached at anissa.patel@winsor.edu