By Frank Conte

The Boston Ledger

Week of November 16–23, Vol. 44, No. 45

[Editor’s note: The author believes this article was published in either 1981 or 1982]

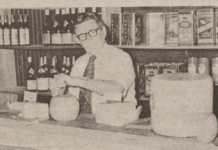

A year from now, Sam Crisafulli will no longer be living on Billerica Street. Neither will another 56 families who have their homes on one of the last surviving old streets of the West End. The humble brick houses in which the people of Billerica Street live will be demolished under a multimillion-dollar revitalization plan. After years of reprieve from final destruction, urban renewal threatens to obliterate the last vestiges of the West End.

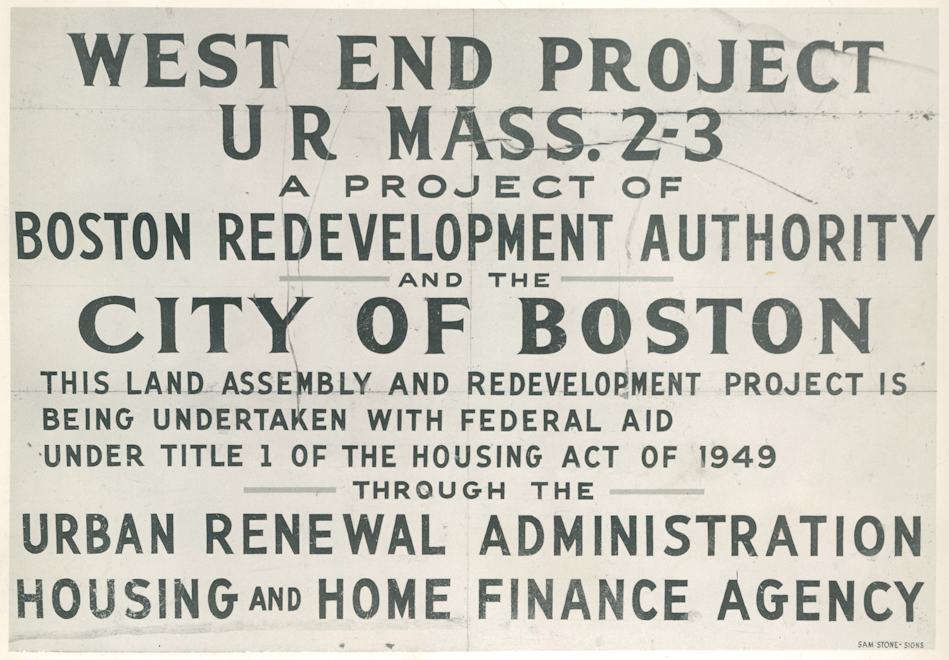

The new arrival is the federal government, in the form of the General Services Administration. Crisafulli will have to trust the Boston Redevelopment Authority to relocate most of the residents on Billerica Street and Lomasney Way. In the 1950s, relocation was a disaster. Most people were displaced outright after the West End was handed over to large-scale developers. The Russian and Bulgarian Jews, the Italians, and the few Black families were dispersed. Today the scenario isn’t altogether different, even if the numbers are smaller.

“It’s a replay,” says Crisafulli. “There are just new characters involved. That’s all.”

Years ago, when the developers and the pro-growth politicians ruled with the power of eminent domain in one hand and big federal dollars in the other, relations between residents and officials were not always congenial. Crisafulli recalls plenty of suspicious fires on the eve of urban renewal in the West End. There were schemes to inadvertently knock down houses while the occupants were away.

Crisafulli remembers vividly the night of December 12, 1959. He came home and saw a wrecking ball in front of his home, ready to take down a building with his relatives inside. Luckily, Crisafulli was able to stop it.

Today things are handled in a different manner, thanks to an era of community activism. Everything is now pre-arranged. Crisafulli himself sits on a Project Advisory Committee (PAC) working with the BRA. Although he maintains he is outvoted on many matters, he tries to make his opinion felt. Some officials are quick to point out that Crisafulli is not afraid to speak out, especially concerning Billerica Street.

Crisafulli does not believe that the power of eminent domain should be used to benefit financiers who are readying to profit from the targeted area. He maintains that Billerica Street and Lomasney Way represent a slice of history. But the new plans and design do not call for retaining and revitalizing the one block that remains of the old West End.

“If developers were brought in to repair and rebuild rather than tear down and destroy, we could be like St. Botolph Street — like the houses behind Copley Plaza. We could build together,” says Crisafulli. But that is not in the plans.

The big plans for the North Station area are being drawn not by people like Sam Crisafulli, but by Moshe Safdie, the architect of Habitat built for the Montreal Olympics and now a special BRA consultant; by Senator Paul Tsongas, who has a proposal for a new Boston Garden; and by the Mayor, who coaxed the General Services Administration into constructing a new “Tip” O’Neill federal office building. The concerns of the West End neighborhood are dwarfed.

Money and Jobs

The future promises big money and plenty of jobs, two pitches which are extremely popular these days. In the City Record, Mayor White says the federal building “will ‘anchor’ the entire North Station project, which is expected to generate more than $400 million in private investment.”

Crisafulli looks at the problem realistically. He knows that he alone can’t stop the development. Peaceful coexistence is not on the BRA’s mind. “I’m not against a new Garden or a GSA building,” he says. But there are other interests at stake. A pro-growth mayor and City Council, a coalition of businesses and real estate people who have recently discovered the value of the neighborhood — if these people were in Crisafulli’s place, maybe they would be more sympathetic. “I don’t know if an injunction is going to convince them but if it came down to that … we would go to court,” Crisafulli says.

The only thing that saved Billerica Street and Loamansey Way from the federal bulldozers of yesteryear was the elevated MBTA tracks. At that time, the “T” was reluctant to change the route of the Green Line because of the expense. Today, the MBTA is thinking of tearing down the elevated tracks and relocating them behind the new Garden site. (When that proposal was brought up years ago as a solution to the tremendous noise in the West End, Crisafulli notes, the MBTA turned a cold shoulder. Now the players are different and there’s plenty of money around to relocate the track — even if the MBTA doesn’t have it.)

The GSA has finally chosen a design for the $90 million North Station federal office. The building will be a mid-rise which will take up more ground space than alternative high-rise plans. The GSA decided not to go with the 22-story building, charges Crisafulli, because real estate speculators have future visions of a high-rise adjoining Charles River Park: a GSA tower would spoil the high-rent cosmopolitan view.

A Neighborhood of Immigrants

Crisafulli remembers the West End as a bustling residential neighborhood made up mostly of immigrants. He can quickly recall the memorable sites: Polish Park, Spring Street with all the little one-story shops (like Salem Street in the North End), Washington High School. Most of these sites fell victim to urban renewal. First absentee landlords let the area deteriorate. Then the emigration of people to the suburbs sapped the remaining life from the neighborhood. “In 1958 they told you don’t fix up your house; don’t make major repairs, only minor ones,” recalls Crisafulli.

The West End project displaced 2,600 families. By 1959, under Mayor John Collins, 10 percent of the city’s land underwent urban renewal. The New Boston had replaced the Old Boston.

Today the story makes good copy in urban planning textbooks. But Crisafulli is no classroom student of urban renewal: he has experienced it first hand. He has seen his Russian Jewish friends pack up and leave for Brookline, his Italian friends move to East Boston, the North End or Revere, and the few blacks move to Dorchester or Cambridge.

The major problem facing the 56 families today is relocation. The BRA says the families will be taken care of. According to Ralph Memolo, the BRA is looking into the possibility of converting some commercial space into housing. When asked if such housing would be placed on the open market, Memolo said, “it would be done specifically for them” (the West Enders).

“I’ve been looking and I haven’t been able to find anything. They want to put us in housing projects,” Crisafulli says. While there is no housing planned in the $100 million North Station Development, some accommodations are expected.

Ironically, two weeks ago the city recognized a new neighborhood called Downtown North. Mostly commercial, it is located on Canal St. It represents the new class. Towards the other end, almost hidden by the MBTA tracks and dotted with parking lots, is what little is left of the West End. While the city and the financial powers that be are busy building up a new neighborhood they are quietly destroying another. But the memories of residents like Sam Crisafulli will live on, even after Billerica Street ceases to exist.